Brazilian Dialogue

Seeds planted for Brazil's recovery

In the heady months following the Puebla meeting (Pope Paul with Latin America's bishops, 1979), the oppressed classes of Brazil founded their own political party, the PT or Workers Party.

The church didn't support PT but it did support the new party through the thousands of base communities springing up all over the country. In these base communities, lay people, sisters and priests in great numbers studied the Puebla document enthusiastically and they saw in PT the chance to realize the justice aims the bishops had sketched out. PT quickly became not only the centre of opposition to the (then) military dictatorship but a fully fledged national party.

By now readers of Brazilian Dialogue will have heard of President Lula's marginalized background in the Northeast, of his earning a living shining shoes, of his late entry into school, of his employment as a metal worker and subsequent work as a union organizer. As PT party leader (three times losing campaigns for the presidency of Brazil), Lula little by little won the hearts and minds of many in the middle class by his moderation, much as Mandela did in South Africa. Only then could the indigent be pried away from the oligarchs. But, though he's no fiery revolutionary promoting violent overthrow (in fact the Brazilian media now call him "Lula, peace and love"), nonetheless his positions on corruption, on the destitution of a large part of the population, on globalization, on the IMF, on the proposed Free Trade of the Americas, are very close to the stance the Brazilian Bishops' Conference takes on all these issues.

A friend sent me clippings over Christmas from Folha de S�o Paulo, a sort of New York Times of Brazil. One article especially caught my attention. Bishop Luciano Mendes, former head of Brazil's Bishops' Conference, reported on that body's recent plenary meeting.

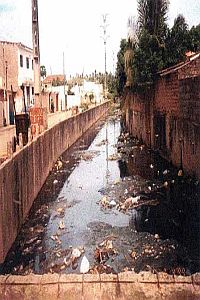

They addressed "the violence and social inequality" afflicting the country. They appealed again to Christians that they practise solidarity, that is, "open their hearts to the needs of their neighbours," to see as brothers and sisters "those fallen beside the road" and to help; to become aware of "the drama in the lives of the unemployed"; to learn "to live simply and frugally, which has the added advantage of being healthy"; to combat "consumerism, the despoliations we practise on nature, the heaping up of wealth."

Mendes cited the holy family's and the first Christian communities' concern for the outsider, their habit of working, their simple lifestyles, their participation in the lives of the people. Listing these goals in this fashion may do them a disservice as each of them merits much reflection and each of them flies in the face of the goals we First Worlders hear promoted each day in the media.

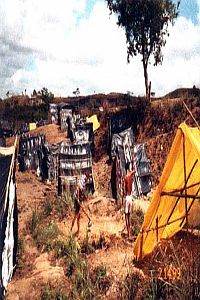

As soon as Lula had appointed his cabinet he took all 30 of them on a visit to the Northeast, in particular to the destitute state of Pia ui (even BBC got it wrong, calling it Pelawi). The ministers were moved, sometimes to tears.

Perhaps Mendes' planting of seeds for the recovery of Brazil's soul will fall on good ground. Both he and Lula agree with Robert Browning, that "life without love is a tomb."

Al Gerwing